Making Sense of Docker in the Easiest Way Possible

So, what’s the big deal with Docker? Well, think about working in a team where everyone’s building the same app but on different machines. Someone’s on a Mac, someone’s on Windows, another’s on Linux. Now imagine everyone having to manually install all the right versions of Node, Redis, and whatever else is needed… in exactly the right way.

Why things go wrong without Docker

When trying to set up an app on a new machine, the first big problem is manual errors. Install the wrong version of a dependency and suddenly nothing works.

The second issue is version mismatch. Maybe the app only works with Node version 16, but someone installs version 20. Good luck getting that to run.

And the third? OS differences. Commands that work fine on Mac might fail on Windows. Multiply that across a large dev team and it’s almost impossible to guarantee everyone’s setup is identical.

This mess even shows up in production when deploying to servers. The famous “it works on my machine” problem comes from exactly this chaos.

Enter Docker and containers

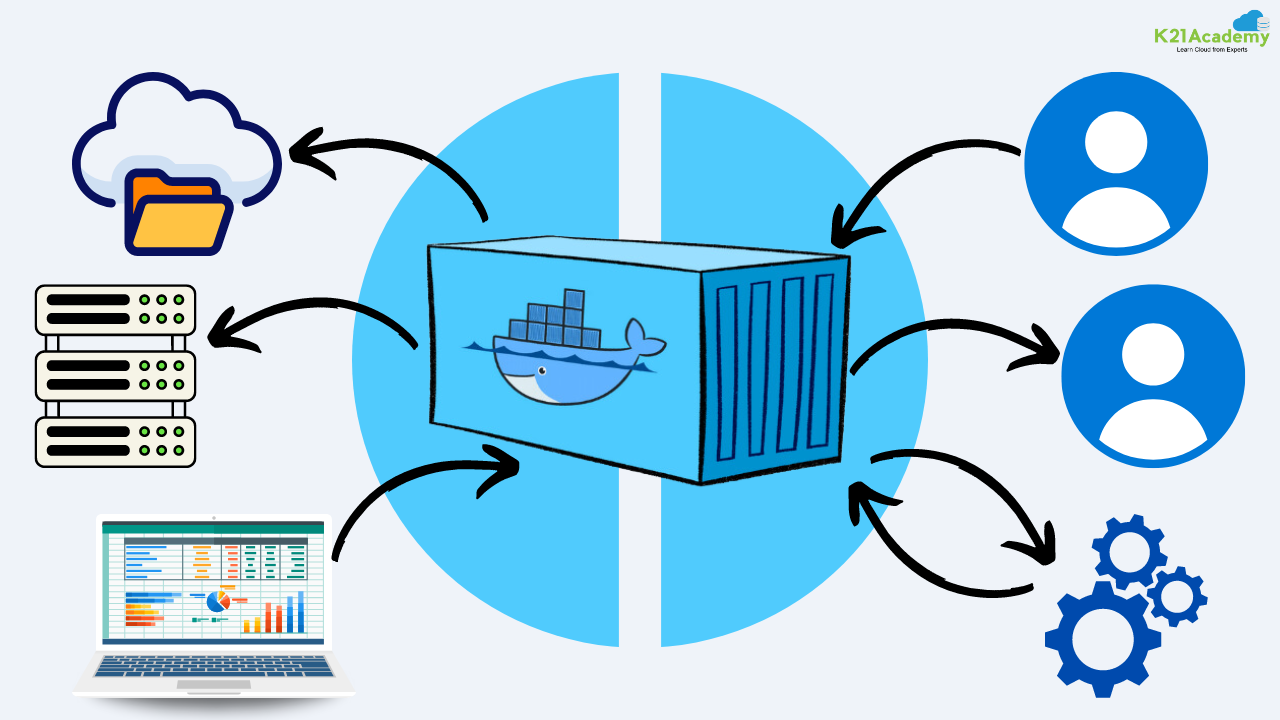

Docker solves these headaches by letting you bundle your app along with all its dependencies into something called a container. A container is basically a self-contained unit that runs the exact same way on any machine—Mac, Windows, Linux—without touching the rest of the system.

It’s like packing everything your app needs into a sealed box. No one has to install things one by one; they just run the box.

Containers have two big advantages:

- They’re portable, so you can share them with anyone.

- They’re lightweight, so they build, run, and update fast.

You could even have two apps on the same machine using totally different versions of Node without interfering with each other.

Docker images and how they fit in

To make a container, Docker uses something called an image. An image isn’t a photo—it’s more like a blueprint. It has all the instructions for how to build the container.

Think of it like classes and objects in programming. The class is the blueprint (the image), and the objects are the actual things you run (the containers).

You share the image, and everyone creates their own container from it. That way, no matter who runs it, the environment is exactly the same.

Running your first image

Docker Hub is like GitHub but for Docker images. You can download ready-to-use images like “hello-world” or “ubuntu” with a simple docker pull command.

After pulling the image, you run it with docker run. Running turns the image into a live container. You can see the container’s ID, status, and even interact with it if you use interactive mode (-it).

With something like Ubuntu, you can actually “step inside” the container’s terminal and create files, run commands, and do development work entirely inside it.

How Docker is different from virtual machines

Many beginners confuse Docker with virtual machines. The difference is pretty big.

| Feature | Docker | Virtual Machines |

|---|---|---|

| Kernel | Shares host OS kernel | Has its own full OS and kernel |

| Performance | Lightweight and fast | Heavier and slower |

| Size | Usually MBs | Can be several GBs |

| Compatibility | Better for same OS family | Works across all OS types |

A virtual machine has its own full operating system and its own kernel, which makes it heavy and slow to start. Docker doesn’t go that far it shares the host OS kernel and only virtualizes the application layer. That is why Docker containers are so much lighter and faster.

Virtual machines can be more compatible across different systems but for development speed and resource efficiency, Docker usually wins.

Why developers love it

Docker takes away the pain of “works on my machine” problems. It makes onboarding new team members easier, keeps environments consistent, and speeds up deployment.

Instead of spending hours or days setting up, you can have a working app in minutes just pull the image, run the container, and you’re good to go.